At What Cost, Excellence?

By Pamela Awad

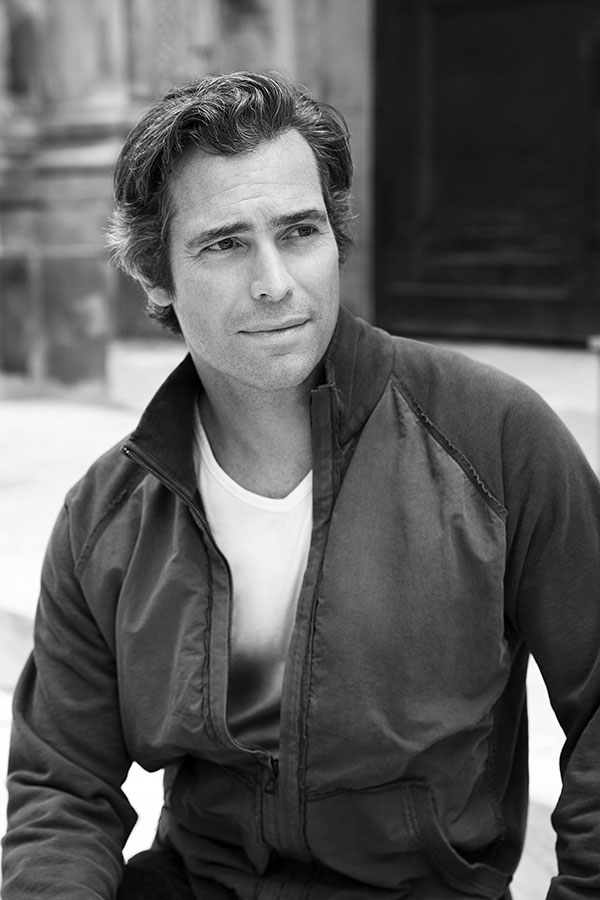

“Fiction is the most powerful way to explore an issue,” Doug Brunt said over lunch recently. It was the second Thursday in November and he was speaking at the NYC-Parents in Action benefit lunch about his third novel, Trophy Son.

“Our youth culture has changed enormously since the time I grew up.” (Brunt was born in 1971.) “I wanted to explore the hyper-scheduling, the intense commitment and the greater parental involvement that we see now.” To do this he chose sports as the vehicle: “Sports is really a bellwether for the youth culture and youth athletics,” and tennis in particular; “the most extreme end of the sports picture. It’s a very narrow, very specialized field of development.”

Brunt is father of an eight, six and four year-old and husband of journalist Megyn Kelly. The inspiration for Trophy Son came when a fellow parent began describing the ordeal of being a chess parent. Both were waiting for their four year-olds to be dismissed from a pre-school chess class when the father began describing the routine of tournament play: waiting for a game to begin, playing the game, waiting for the next game, playing and waiting every day of the week-end, most weeks of the year. Brunt decided this was the stuff of which novels are made and Trophy Son was born – a story about a tennis prodigy and the father who maniacally grooms him to be the best tennis player in the world.

While researching the book, Brunt wondered if this trend towards early involvement in sports was good for the sports business. Speaking to the CEO of the sports equipment company, Rawlings, he found quite the opposite. Kids are no longer multi sport athletes and the purchasing of athletic equipment is no longer seasonal, it’s an “or,” not an “and” game; kids now play one sport only and purchase equipment accordingly- a baseball mitt or basketball, a soccer ball or tennis racquet. And as kids miss out on the benefits of multi sport play, grandparents feel a loss too. At many stops on his book tour grandparents were “lamenting the lack of time they have with their grandkids, (saying) if I want to see my grandkids I have to go to the sidelines of the soccer game.” These exchanges,” he says, were “ touching, endearing and a little sad.”

Dressed in a navy suit, white shirt and brown striped tie, Brunt talked about the “cultural infrastructure” that determines a child’s athletic success and looks something like this: Your eight year-old joins the travel team (which means both weekday and week-end practice) in order to qualify for the nine year-old travel team, so she’ll be able to play well at increasingly competitive levels as she gets older. Brunt feels “it’s a narrower way to grow up and there’s no kids getting bored and figuring out for themselves how to get un-bored.”

The book he, said, is not “a scathing assessment of youth athletics,” but a warning about the pitfalls of obsessively pursuing a single sport from a young age. He believes athletics teaches teamwork, discipline and other life lessons, but he doesn’t want these attributes to be learned at the expense of a broadly focused or varied childhood experience. “I’m very much for passion and concentrated effort. I want to see kids’ eyes light up with enthusiasm for an activity.” What he opposes is the “systematic requirement for early specialization,” that seems to be the standard today.

Brunt sees two categories of problems developing from the current trend in youth athletics. Intensive training at a young age can cause physical problems including an increase in stress fractures and other overall injuries. When these injuries are treated with pain medication, there’s a risk of overprescribing and subsequent addiction that in turn feeds into the nationwide opioid epidemic. But the novel focuses on the mental and developmental problems that result from the all-consuming nature of specialization. “A narrow field of development in those teen years can be dangerous,” Brunt says; young athletes may be left emotionally unprepared to handle new situations and, socially, years behind their peers, particularly if they’ve left the academic mainstream.

There’s a legendary story that a frog is impervious to the danger of water slowly heated to boiling. Brunt uses this as an analogy for how we got to this place of high expectations and early specialization. He says the “slow acting reasons” include the allure of pro sports in terms of money and celebrity; an increase in disposable income that allows parents to support their child’s efforts and/or vicariously live through him or her; today’s heightened level of parental involvement in our “tiger mom” culture; and, lastly, the changing expectations of college admissions boards who now look for students of exceptional achievement in one area, rather than students who are well-rounded. And while parents are usually well- meaning, their efforts may be misguided.

“Drive, drive, drive isn’t better, better, better; at a point it’s actually disruptive,” he warns. Brunt thinks communication and awareness are the keys to change and while it may be slow in coming, change is in the air. The more parents talk to each other and to their children’s teachers and coaches, the easier it will be to change cultural expectations. Finding a passion and excelling at it at the expense of doing something (or nothing) for the fun of it leaves little room for discovery and play. “Of course you have to practice, have to play, have to get good,” said Brunt, but it doesn’t have to be all consuming and kids shouldn’t have to miss out on other things. “By the time I’m a granddad, I expect to be spending a lot of time with my grandkids.”